I recently secured a patent for an idea to make our public transit systems more fuel efficient, reliable, and comfortable for users. Here’s the origin story.

You might say the story started 25 years ago in the American Society of Civil Engineer’s (ASCE) lounge at University of Maryland. A bunch of us who were about to graduate were talking about what we wanted to do with our futures. I blurted out that I wanted to invent something. Maybe this stemmed from me wanting to change the world, but it also was likely my naiveté showing up!

In reality, I spent the first decade of my career learning. I say the first decade because I invented a new type of interchange in the 2000s. Transportation is a complex system, and it takes time to learn, carefully observe, test, and then finally innovate and invent—you normally don’t just set out to invent stuff; it doesn’t work that way in my experience. The proverb “necessity is the mother of invention” has been true in my cases. The invention and subsequent patent was birthed out of a real need and problem I was trying to solve. The real innovation process was much more like my day-in, day-out work of being a problem-solving engineer. A patent sounds really cool and fancy, but in reality, it is just good-old, solid engineering problem-solving. It’s the same work that we here at Mead & Hunt do all day, every day. In that sense, I’m not unique…I was fortunate to be the one with a problem that needed solving!

So, back to the origin story…

Mead & Hunt had a project to improve the Light Rail Train (LRT) travel times by improving the traffic signal operations on a corridor in downtown Baltimore, Maryland. Our goal was that the LRT would never stop at a red traffic signal—only green lights for trains! So, we implemented the latest and greatest technologies such as preemption, transit signal priority, and passive signal timing to adapt the transportation infrastructure to give priority to the transit vehicle. We got some great results, but I thought it could be better. Namely, because I designed the signal timings, I knew exactly when the drivers needed to hurry up and leave the station to hit the next green signal, or when they needed to slow down because the next signal wasn’t going to turn green right away. In other words, there was a human element. I thought, if only I could drive the train, I would drive the train to hit all the green lights and minimize the number of stops to give passengers a smoother, more pleasant ride. Of course, I can’t drive a train, but the idea that I could somehow communicate to the driver when the traffic signals would turn green for the LRTs in time and space is the birthplace of the invention.

Thus, the idea for the patent, “Onboard Eco-Approach and Departure (EAD) for transit vehicles” was born. We won a Federal Transit Administration (FTA) project to develop the idea in partnership with Traffic Technology Services (TTS). Many thanks to TTS for financing the cost of obtaining the patent!

How does it work?

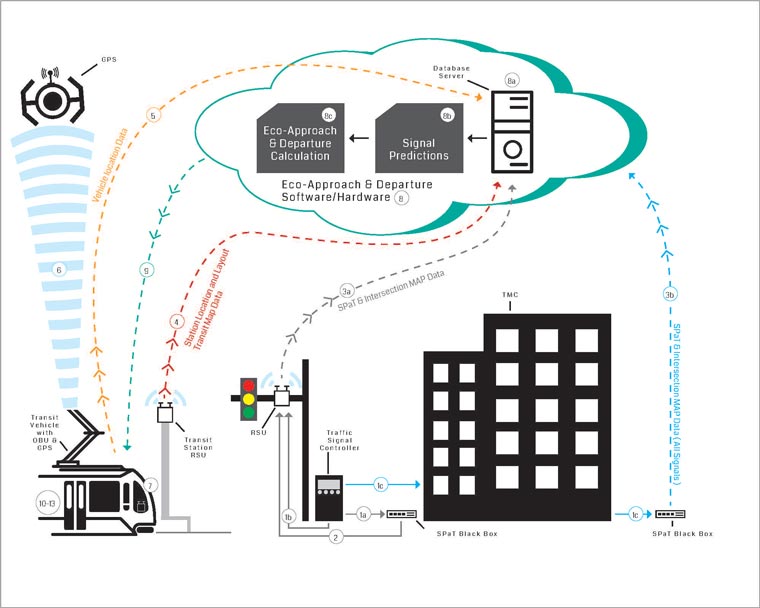

The idea developed a methodology for reviewing the real-time location and route of a transit vehicle, correlating these with real-time and predicted signal phasing and timing (SPaT) information from traffic signals, and communicating information to transit vehicles through onboard Mobile Data Terminals (MDTs). These are components of the connected vehicle (CV) ecosystem where real-time data is exchanged between infrastructure (traffic signals in this case) and vehicles (LRT) respectively.

While traditional measures focus on manipulating the environment outside of the transit vehicle, this idea is different in that it rests on adapting the behavior of the driver. Using signal timing data and traffic patterns saved in the cloud, we can make predictions that we can then turn into actionable items and information to empower drivers. For example, our system might tell the driver to wait 20 seconds at a green light, or only drive 15 miles per hour (mph) versus the 25-mph speed limit. These actions then result in the transit hitting fewer red lights, providing a smoother ride for users, and enhancing fuel efficiency by reducing the number of starts and stops taken overall.

Why does it matter?

Nearly half of the total passenger miles on public transportation systems traverse signalized intersections. Consequently, travel time and reliability of public transportation is significantly impacted by traffic signal system operations along the transit routes. Several studies of transit systems indicate that up to 40% of these delays can be traced to delays at traffic signals. These delays lead to longer travel times and contribute to higher energy consumption due to the increased stops and starts necessitated.

In addition, for public transit, perception is important. It matters how people feel about using these services. This means that, when it comes to ascertaining how effective service is, we need to account for qualitative as well as quantitative measures. And we’ve found that the level of quality and number of stops have an inverse relationship; as the number of stops goes up, the perception of quality goes down, even if the actual ride time is nearly the same. In the simulations we ran, not only did EAD for transit vehicles increase ride quality, but it also decreased travel time and enhanced reliability. Reducing the number of starts and stops taken by public transit enhances fuel efficiency, leading to reduced cost on fuel, as well as reduced carbon emissions—hence the “eco” part of “Eco-Approach Departure.”

Where are we now?

This application serves to connect roads, humans, and vehicles—it therefore acts as an effective bridge between existing and future Connected Vehicle (CV) environments. Although future CV technology is anticipated to maximize the productivity of the system, it is not expected to be fully functional until 2040 or later. There is a need and market for a product to reduce delay, improve safety, mobility, economic competitiveness, and environmental sustainability of transit vehicles. Practically speaking, we have the technology necessary to implement this idea now. There is quite a bit of interest, so while budgets have been on hold the past year and a half, we are hopeful that with time there will be funding in place to deploy.

I am very happy to have been part of this process, along with my teammates Kiel Ova, Venkat Nallamothu; Thomas Bauer; and Jingtao Ma—and to be in a position where I have the capacity to work to make our transit systems better. The human factor, the ability to improve human life in some way, for me, is what it’s all about.