As Mead & Hunt celebrates its 125th anniversary, I’m impressed by the depth of historical knowledge our company has in the field of American military aviation. That story begins in the 1940s with propeller-driven fighters and leads us to today’s artificial intelligence-driven autonomous aircraft that would have seemed like science fiction 80 years ago.

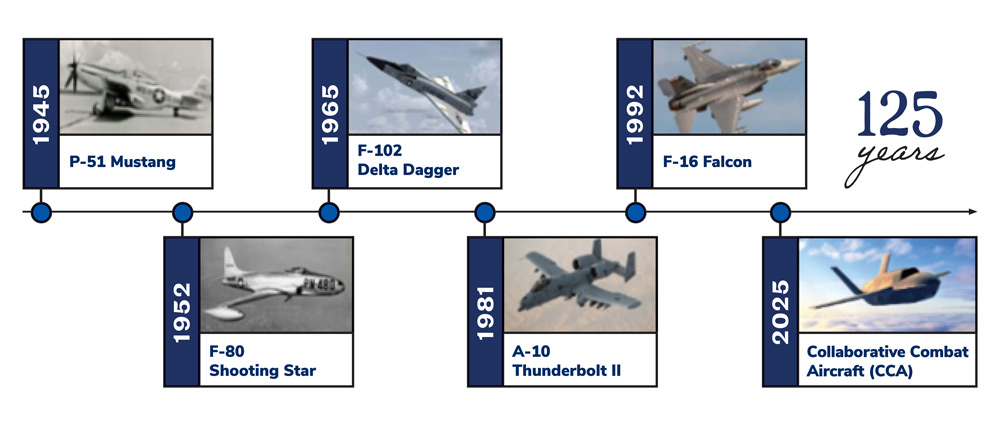

I’ve dedicated my career to military planning, and what strikes me most is the continuous thread connecting our work from those early days at Truax Field in Madison, Wisconsin, to our current cutting-edge projects at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. When I tell people that our company has supported aircraft from the P-51 Mustang to today’s unmanned aircraft, I see the recognition in their eyes—especially from those who understand aviation history. Mead & Hunt has had the privilege of being part of the evolution of military aviation, helping advance and develop the supporting infrastructure that makes the successful beddown of these new airframes possible.

From Truax Field to Modern Military Aviation

In the early 1940s, as the nation mobilized for World War II, Mead & Hunt took on the challenge of expanding Truax Field in Madison, Wisconsin. This project meant rapidly building the infrastructure needed to train the pilots who would help win the war.

In the decades that followed, we partnered with federal military airfields through every major transition in military aviation technology. We supported operations for aircraft that defined entire eras, including the P-51 Mustang, the F-80 Shooting Star that ushered in the jet age, the F-86 Sabre that fought in Korean skies, and supersonic fighters like the F-102 Delta Dagger and F-106 Delta Dart that stood guard during the Cold War.

Our portfolio has expanded far beyond the original fighter planes. We’ve planned and engineered projects for the full spectrum of military aviation, including B-52 Stratofortress bombers, C-17 Globemaster III cargo haulers, B-1B Lancer supersonic bombers, and the workhorse C/KC-135 Stratotankers. These aircraft have conducted military missions that have saved more lives than we may ever know.

Creech Command Center: Where Critical Flight Missions Begin

Creech Air Force Base is a prime example of a facility that remains at the forefront of military aviation. Since its inception in World War II, it has served various purposes through the years, including as a practice site for the Air Force Thunderbirds and divert field for all things in the Nevada Test and Training Range. The base underwent a significant shift in the late 1990s and early 2000s when the Air Force introduced remotely piloted aircraft (RPA). The first flight of the RQ-1 Predator drone positioned it to become a global hub for RPA operations.

Today, the base’s primary mission is advancing aviation technology. The base serves as a command and control facility, where airmen remotely pilot aircraft for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions, precision strikes, and close air support for ground troops worldwide. It’s also a major center for RPA units dedicated to testing and evaluating new technologies and procedures for RPAs. The base continually deploys new versions of RPA with enhanced capabilities, such as the Block 5 MQ-9 Reapers.

Ushering in CCA, NGAD, and the Future of Air Superiority

Currently, we are supporting the Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program at Creech and recognize that traditional infrastructure planning methods need to evolve. Operational requirements for autonomous CCA present unique demands that challenge the established norms of military aviation. The introduction of this new class of weapon systems makes us reassess everything from hangar layouts to communications networks, leading to meaningful conversations on how innovation can reshape defense practices for the future.

The CCA program is the opening act for an even bigger change on the horizon. The Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program will produce the F-47, the aircraft that will eventually replace the F-22 Raptor. The concept of manned-unmanned teaming represents the future of air superiority. The F-47 will bring human judgment and adaptability to the fight, while CCA platforms provide force multiplication and enhanced sensor coverage.

What excites me most about working on these programs is the forward-thinking nature of the planning. While the Air Force designs for today’s requirements, we in military planning look 15 to 20 years into the future, anticipating the next generation of aircraft and the generation after that. Planning infrastructure for programs that will define our nation’s air superiority for decades to come is a responsibility that connects directly to national security and the safety of our nation’s air combat specialists.

Our veteran-led team gives us an innate understanding of military culture. We recognize the deep reliance and trust that exist within military teams and the schedule discipline that defines military operations. This insider’s perspective not only allows us to plan facilities for unmanned aircraft but also offers an invaluable perspective that goes beyond technical expertise. Our veterans know that behind advanced aircraft and autonomous systems are people who rely on infrastructure that supports those who execute these lifesaving missions.

In Reflection

Looking back over 80 years of supporting military aviation, from those first expansions at Truax Field to today’s autonomous aircraft programs at Creech, I’m struck by how much has changed yet also what has remained constant. The aircraft have evolved from propeller-driven fighters to AI-powered autonomous platforms, but our core mission remains unchanged: to provide the infrastructure and expertise that allow our military aviators to succeed.

That’s the important thread connecting our past to our future, and one I’m proud to be part of as we continue charting the course into the next era of military aviation.