In the 1970s and 1980s, Tampa Bay was experiencing a pollution crisis. Water quality had been on a steady decline for decades: water clarity was poor, algal growth was rampant, and once-abundant sea life was noticeably absent. Many feared that the bay had been ruined for good and there was little hope of recovery.

It seems history is repeating itself. We are now seeing similar headlines about water quality in the Lake Okeechobee watershed and its downstream estuaries. Florida has overcome this challenge before—by leaning on lessons from our past, we can overcome it again.

What went wrong?

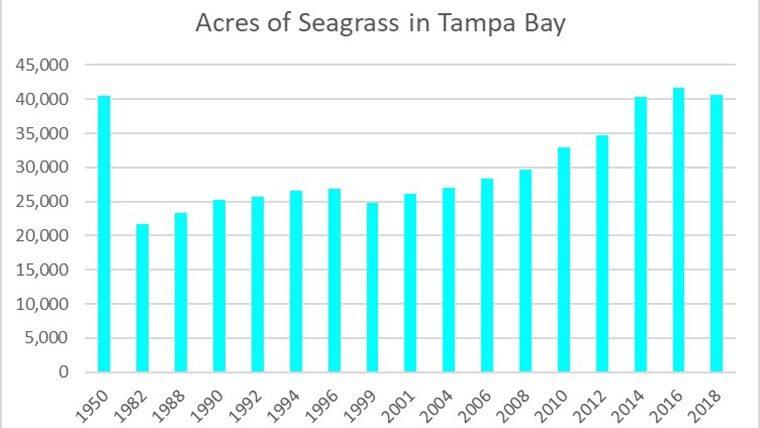

From 1940 to 1970, the population in Tampa Bay nearly quadrupled, growing from roughly 312,000 to over one million people. This led to increases in wastewater discharges and stormwater runoff, which increased the nutrients, most notably nitrogen, flowing into Tampa Bay. Excess nitrogen spurred algal growth, which reduced water clarity and depleted dissolved oxygen in the water, which then caused fish to suffocate and die. In addition, reduced water clarity prevented sunlight from reaching seagrasses which serve as critical sea life habitat in the bay. Seagrass coverage decreased from nearly 40,000 acres in the 1950s to a low of 21,600 acres in 1982.

Collaborative solutions

In response to worsening conditions in Tampa Bay, the state legislature passed the Wilson-Grizzle Bill in 1972, requiring advanced wastewater treatment for any plants discharging effluent into Tampa Bay and its tributaries. In 1979, the City of Tampa opened the Howard F. Curren Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant (AWTP). The new AWTP produced effluent so clean that City officials drank the effluent from champagne flutes to celebrate the opening. On the opposite side of the bay, St. Petersburg established one of the nation’s first large-scale reuse systems which used treated wastewater for irrigation, reducing overall wastewater discharges to the bay.

In 1990, Tampa Bay was accepted into the National Estuary Program and in 1991, the Tampa Bay National Estuary Program (TBNEP) was established. In 1996, the the Comprehensive Conservation & Management Plan (CCMP) for Tampa Bay was approved and established numeric goals for water quality improvement in the bay and laid out specific strategies for reducing nitrogen loads to Tampa Bay from runoff. The CCMP identified seagrass as a key indicator of water quality in Tampa Bay and set an aggressive goal to restore seagrass levels to 38,000 acres. To meet these goals, regulators at the local, state and federal levels, along with local municipalities, utilities, landowners and private companies, entered into a public-private partnership called the Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium.

Through this commitment to collaborative efforts, good things started to happen: nitrogen levels began to decrease, water clarity increased, and seagrass growth started coming back. Since 2001, Tampa Bay has seen continual increases in seagrass coverage and in 2015, actually met the goal set by the CCMP. As of 2018, seagrass coverage in Tampa Bay was over 40,000 acres.

Looking ahead

As we examine the current water quality in the Lake Okeechobee watershed, its downstream estuaries, and other water bodies around the state there are unmistakable similarities to Tampa Bay in the 1970s and 80s. The good news is that this problem is not insurmountable. As we’ve seen from our past, we have the ability to successfully overcome water quality challenges.

Next month, we will post an article that discusses some of the current nutrient loading challenges in Florida and how regulators, municipalities, and environmental professionals are planning and working to protect our natural resources. As environmental professionals, we can lean on the success in Tampa Bay to provide an example of how collaboration and commitment can help us reach goals that may currently seem out of reach.