February is Black History Month. As part of our series focusing on underrepresented groups, I am highlighting recent efforts in Tulsa to understand a race riot and share my experience in interpreting this event to others.

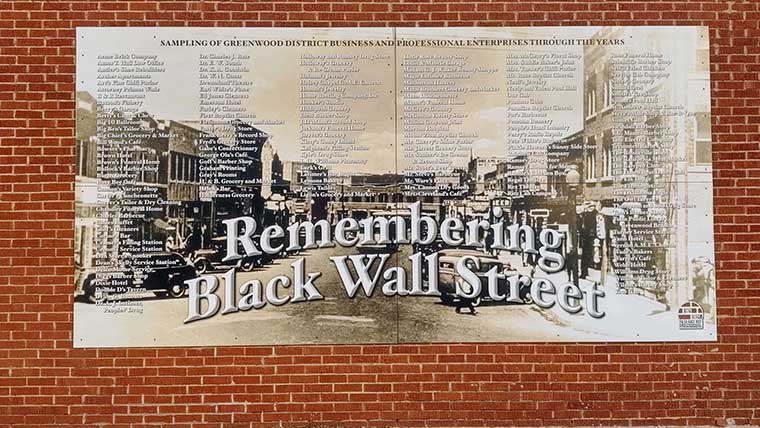

By 1921, Tulsa, with its oil boom and Art Deco buildings, was one of Oklahoma’s most vibrant and modern cities. Most of the city’s 10,000 black residents lived in the Greenwood District, a thriving neighborhood that contained numerous black-owned businesses. The district was one of the most well-known and highly concentrated areas of African American businesses in the United States—so much so that it was colloquially known as America’s “Black Wall Street.” That is, until the Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed it.

It’s a tragic and sobering chapter in Tulsa and U.S. history whose details were not commonly known until recently.

Forgotten history

In the 1920s, Tulsa mirrored national trends of racial tensions as black communities fought against discrimination and violence, including lynching. Against this backdrop, a simple misunderstanding in Tulsa’s bustling downtown ignited tragedy.

Dick Rowland, a black man, shined shoes in a downtown parlor. Rowland’s boss arranged for black employees to use the restroom on the top floor of the Drexel Building, where Sarah Page, a white woman, operated the building’s only elevator. On an elevator trip Mr. Rowland accidentally jostled Ms. Page, causing her to yell out. The encounter resulted in a false accusation of attempted rape.

The event escalated even further when an angry mob of white men hunting for the young man was turned away outside the courthouse by local guardsmen. The mob turned its animosity on the black community. Shots were fired and the city descended into chaos. Over the next 18 hours, estimates of up to 300 black people were killed, and more injured. Mobs poured through the streets, looting businesses and burning homes of black residents in neighborhoods of the Greenwood District. Local authorities did little to stem the violence.

During the ensuing chaos Rowland was protected in the courthouse jail, and moved to Kansas City once he was released and exonerated of charges. Page also survived and they both slipped into anonymity, until recently. The Greenwood District was almost completely destroyed, and generations later Tulsa has yet to fully address the event that became known as the Race Massacre. Sadly, the grave sites of most killed in the violence went unrecorded.

Acknowledging an ugly truth

For most of the remaining twentieth century, this horrifying event was largely ignored and barely mentioned in history books as generations of Tulsans/Oklahomans grew up unaware of this chapter of their history. This began to change in recent decades as Tulsa’s diverse population sought to acknowledge and better understand the lost history. A study commissioned in 1997 investigated the events; the Tulsa Race Riot Study was completed in 2001 (the event was later renamed the Tulsa Race Massacre). One chapter of the study explored the number of victims and outlined preliminary work to identify potential mass grave sites.

By the 2010s the Race Massacre became widely known as local and national media aired the story. I learned more about Tulsa’s forgotten history at the 2018 Oklahoma Preservation Conference in Tulsa, where a track of sessions was dedicated to the topic of the history of the Race Massacre. The sessions shared valuable information from the historic record of events, and also suggested that important work still needed to be completed: namely, to find the lost victims. Present-day city leaders began an initiative in 2019 using modern tools to identify grave sites to begin to heal the wounds this event caused.

Like many Tulsa residents, I’ve watched the initiative to find the gravesites of victims on the news with interest. This past fall, teams from the University of Oklahoma’s Oklahoma Archeological Survey scoured three sites with ground penetrating radar to identify possible graves. Further testing will start as weather allows. If mass graves are found, study of remains can potentially lead to better understanding of the event, and identification and reburial of victims. These important steps in acknowledging the terrible event will hopefully lead to healing.

Moving forward

Since moving to Tulsa I have helped with a Tulsa Foundation for Architecture (TFA) tour of the Greenwood District, the area formerly known as Black Wall Street, highlighting the few extant buildings from that period—beginning at the Greenwood Cultural Center next to the Mabel B. Little Heritage House and ending in the John Hope Franklin reconciliation garden.

The tour stopped at several buildings along the way, including commercial properties and churches where descendants of survivors, and others prominent in the black community, spoke. It was very moving and highlighted the intense emotional trauma that the ugly history of race relations, discrimination and racial violence can have on a city and descendants even generations later.

My experience in learning about Tulsa’s Race Massacre, and my limited involvement in bringing this sad but important event to light, is my way of understanding Black History Month this year. Everyone, but public historians especially, need to more fully incorporate the histories of black Americans in National Register nominations and, by extension, in historic preservation and cultural resources management. I hope others will benefit from the steps Tulsa is taking to provide a more complete history of Tulsa and the tragic events of the Greenwood District of almost 100 years ago. I encourage everyone to explore ways to better understand the layered history of cities and that of underrepresented groups.