When Daniel Mead started our firm in 1900, traffic engineering was a thing of the future. 125 years later, transportation challenges have evolved, but our priorities are still getting people where they need to go safely and efficiently. Here’s a look at how transportation technology improved the traffic signal from a simple safety device to an intelligent system, and where I think we’re headed next.

From Hooves to Horsepower

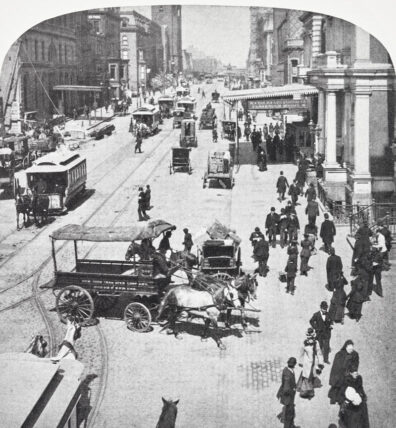

A traffic study in 1885 counted nearly 8,000 horse-drawn vehicles at the New York City intersection of Broadway and Pine Street on a typical day. At the time, cars were a novelty for the rich. By comparison, there were only about 8,000 in the entire United States. During this time, America was in transition from an agricultural society to an industrial nation. In cities, Americans usually moved by horse and buggy and electric trolley. Long-distance travel was reserved for trains and boats.

The nation’s roads were mostly dirt, often thick with mud and unpassable, posing an economic problem for the 60% of rural Americans who needed to take agricultural goods to market. Not only were our roads in bad condition, they were also dangerous and often filthy.

In New York City in 1900, horse transportation killed 200 people, and horses left behind 2.5 million pounds of manure and sixty thousand gallons of urine per day. The horse was not a new problem, as Julius Caesar banned horse-drawn carriages in ancient Rome for these same reasons. The demand for better roads was rooted in the need for improved health, safety, and economics.

Americans fell in love with the automobile, and vehicle ownership exploded to over 8 million vehicles by 1920. However, all these new vehicles caused major congestion. In his book Big Roads, Earl Swift notes that, “By the late 20s, traffic congestion had grown into one of the greatest vexations of everyday life in all of big city America.”

Enter the traffic signal—adapted from the railroad signal—to solve the urban safety and congestion crisis. The first electric traffic signal was installed in 1914, and the yellow “warning” light was added in 1920.

The traffic signal is fundamentally a safety device whose purpose is to alternate the right-of-way. The tri-color red, yellow, and green traffic signal was standardized in the 1935 Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD). Uniformity created greater safety on the roads. Early traffic control devices, specifically signals and signs, took whatever form the inventor came up with, which presented a different safety problem. Drivers either interpreted them differently, or it took more brainpower to understand the message and react.

Seamless travel across states required predictable rules, and MUTCD became the backbone of that system.

New Rules of the Road

Americans kept buying cars throughout the 1920s and 30s. Crash rates skyrocketed during this period, reaching an all-time high. Think about how central the fatal car crash is in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. In fact, they were a greater problem than today considering the population was one-third of what it is today, and Americans drive 15 times as many miles now as back then.

Some of the first traffic sensors were invented during this period. These sensors detected a vehicle and changed the signal to green. Early inventions included pressure sensor plates that identified the weight of a vehicle, and sound-based systems that required drivers to honk their horn.

The 1920s also saw the beginning of coordinated signal systems so that drivers could get progressive green lights. However, these systems were pre-timed and did not adjust based on real time traffic demands. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that the new technologies of traffic detection, analog computers, and coordinated signal systems were combined to respond to traffic flow. Over 100 computer-based signal systems were installed in America between 1952 and 1962.

Traffic congestion was still a major problem in the pre-interstate years. By 1962, we had only 30% of the 46,876 Interstate Highway System miles that we have today. Eisenhower is often credited with our Interstate Highway System, but a little-known fact is that it originated during the Roosevelt administration in a 1939 FHWA publication Toll Roads and Free Roads. While President Eisenhower signed the landmark Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 to authorize the system, he did not invent it.

During the post-war years, the signal system evolved once again to address continued safety issues and arterial congestion. Adapting systems to traffic flow became linked to traffic detectors and computer algorithms. All systems, even modern ones, use traffic detection to sample key statistics such as volume, directionality (e.g., inbound in the AM peak, outbound in the PM peak) and other metrics, such as length of the queue or average wait time at a red signal. This shift toward adaptability marked the beginning of a philosophy that still drives transportation today: technology should serve people, not the other way around.

The Signal Gets Smarter

When I entered the field of transportation engineering, traffic signals were already ubiquitous—there are roughly 330,000 signals in the U.S. today—but their intelligence was limited. Most relied on inductive loops buried in pavement, detecting vehicles by changes in magnetic fields. It worked, but every repaving meant reinstalling loops, and failures were common. I’ve watched detection evolve from those loops to video cameras, to video cameras with thermal imaging that addresses fog and sun glare, to combination systems with microwave radar and video.

Today, we classify and track vehicle movements and even predict arrivals using artificial intelligence (AI). The biggest changes in signal systems are the ubiquity of vehicle location data. Traffic engineers are moving away from point detectors on the road to access real-time data and statistics in the cloud. These data will improve the ability of signal systems to respond to changing traffic volumes in advance of traffic surges arriving at the signal.

However, with connectivity comes vulnerability. Cybersecurity is now as critical as signal timing. What was once a simple electromechanical device is now part of a digital ecosystem, and that comes with its own set of concerns. History teaches us that every advance brings new challenges. During the Cold War, spies in Poland preempted plans to disable the traffic signals to impede the expected invasion. In modern times, we have cybersecurity to prevent bad actors from hacking our traffic signals to congest our cities—like in the movie The Italian Job—as a method to potentially disable a city.

Alongside these smarter signals, we’re implementing additional security measures to prevent issues before they affect drivers.

Transportation’s Tech-Driven Future

So what’s the next destination on the road to advancing traffic signal technology? I believe the future lies in integration. We’ll go beyond smarter signals to full systems that talk to each other, anticipate demand, and adapt in real time. Connected and autonomous vehicles will redefine intersections. AI will optimize corridors dynamically, balancing safety, mobility, and sustainability. And yes, cybersecurity will remain front and center.

Progress isn’t just about technology—it’s about people. Our job is to make movement safer, smarter, and more reliable. Partnering with communities to improve infrastructure is what Mead & Hunt has done for 125 years, and we’ll carry that forward as transportation enters its next era.